-

-Most readers do not get past page 18 in a book they have purchased.

-70% of US adults have not been in a bookstore in the last five years.

-The time Americans spend reading books 1996: 123 hours 2001: 109 hours

-Used books were purchased by one out of ten book buyers in the previous nine months in 2002.

-Used books account for $533 million in annual sales; 13% of the units sold and 5% of the total revenue. The heaviest book buyers buy more than one-third of their books used.

-The largest-selling used books are: Mysteries, romance and science fiction. Used nonfiction sell best online.

-A successful fiction book sells 5,000 copies

-1.5+ million titles in print (currently available in the U.S.) Since 1776 22 million titles have been published.

The book industry statistics listed above are from a recent post at Dan Poynter's parapublishing.com. The original post has many more fascinating facts about the publishing industry, sales, the used book industry, reading, and much more. While I'm not fond of statistics, since they almost always seem counter to the actual reality I live and work every day, they do provide a certain interest and get the brain working.

Statistics are useful lies that get us to thinking about the truth.

For example, I'm not suprised that 70% of people have not been to a used bookstore in the last five years. Why? Because they spent the money they would have spent on books going to see Titanic, Lord of the Rings, Shrek and Spiderman. Plus, so many people think of reading books are something that is "hard" to do. You actually have to "read", whereas in the movie theatre or at home watching TV you just sit there and the movies do all the work. And it's so much easier to just look at big pictures rather than having to read words one after the other. I'm being cynical, of course. But I think you get my point.

What's cheering about some of these facts (and I can attest to in my daily work at the bookstore) is that more people are reading than ever before. I'd rather they were reading Tolstoy than Nora Roberts, but at least folks are reading. And while the statistics suggest that older people are more likely to frequent used bookstores, this is not the case in my experience. In my 30+ years of bookselling, I've always seen a large turn out of young people. Of course, they are sometimes there because they have to pick up books for summer reading, or are looking for a cheaper copy of a required book for class, but they are IN a bookstore which is a dangerous place to be. They might actually stumble across that copy of Thoreau's "Walden" or R.D. Laing's "Politics of Experience", which would corrupt them entirely with new ways of thinking.

People ask me all the time if books will ever become obsolete. I don't think so. There is something unique and personal about a book that it's digitization can never duplicate. Our culture still values whats original and unique. And books are some of the most unique creations of civilization. They are little mind bombs set to go off in your head when you least expect it. Even our free books set out in boxes in front of the store, regularly disappear. No, books are more popular than ever. And as long as we value the imagination, books will always be the best way we have to communicate and express our thoughts and creations.

Of course, there are those who think the exact opposite: books are an obsolete form of communication. One of the more interesting blog posts that counters my argument that books are here to stay is one by Jeff Jarvis. His "BuzzMachine" blog is highly intelligent and worth a read. Perhaps Jeff should write a book? Oh...I forgot, books are becoming obsolete. Ah, well.... -

I was cleaning out one of my storage drives on my computer the other day and discovered photos I had taken at the L.A. Vintage Paperback Show back at the end of March. I was going to do a booklad entry on the show, but it occured right in the middle of our big bookstore move and I forgot all about it. Well, better late than never I suppose.

I've always loved paperbacks. In fact, my first bookstore job was in Humphrey's Paperback Shop near my home. I spent so much time there pawing the Ace doubles and eye-balling the lurid Gold Medal covers that Hump finally said, "Hey, you kid. You want a job? You're here enough". And that was the beginning of second career as a bookseller. AND it began my great love of what we now call "vintage paperbacks". You know, those old paperbacks with the covers that scream out at you in used paperback shops? Something like this:

Hump didn't much care if I oogled at all, he just wanted me to watch the books and take care of the money while he was out enjoying his retirement. There was a lot more work than I had imagined. Moving boxes, cleaning shelves, alphabetizing, dodging the silverfish in the bags of old, smelly paperbacks that people wanted to trade, cleaning the bathroom, balancing the cash register. Aw, it wasn't that bad. I managed to find time to read such classics as "The Fast One" by Paul Cain, "Dr. Bloodmoney" by Philip K. Dick and "The Yellow Claw" by Sax Rohmer.

But it was the covers that led me to these wonderful words of sleaze, booze and the supernatural. They were like magic doors decorated with wonderous figures that writhed and beckoned. I'm still a sucker for a good cover. I still buy books soley on their covers. Of course, I know the cover often has nothing to do with the book itself. I'd be suprised if the cover artists for these marvelous paperbacks actually read the book they were doing the art for.

After serving my apprenticeship with the Hump, I began collecting paperbacks myself. Doc Savage, Raymond Chandler, Conan, Lin Carter, Andre Norton, and tons more began to pile up in my bedroom until I was often surrounded with these little gems with the screaming covers. I became so addicted to them that I almost always had one with me. This eventually became a kind of neurotic fixation so that I had to have a paperback book with me at all times, especially in public. It was a harmless security blanket for me, but eventually I broke myself of the habit (and thanks to my partner Lisa for her patience).

Before I became the paperback freak, I studied the history of paperbacks and learned the names of the major paperback artists. There wasn't the same interest then as there is now in vintage paperbacks. My love of comic books closely paralled the paperback fixation. Eventually, I was put in charge of the vintage paperbacks at a major mystery store here in Los Angeles. For two years I bought and sold paperbacks. I discovered that there was a large, underground community of people like myself who shared my passion for paperbacks. I attended famous three day paperback show in Portland called the "LanceCon" back in 1996. It was named after Lance Casebeer (yes, that is his real name) who was probably the most important person in vintage paperbacks at that time. In addition to running this great show each year for over a decade, he had the largest personal library of paperbacks in the world with well over 100,000 paperbacks. He often boasted of having every paperback published from the forties to the seventies. If you walked through his attic library where they were all stored, you'd believe it.

Sadly, Lance died a few years ago and LanceCon is no more. But my three days there were some of the most interesting of my life. Talking with other paperback lovers, sharing book titles and arcane info on writers and paperback artists. Buying, selling drinking,eating, laughing. It was all great fun. I ended up buying almost two thousand dollars worth of books and shipping them back to the store where I sold half of them in two weeks. It was a heady and exciting time.

But, let me get to the point of this blog: The Los Angeles Paperback show. This show has been going on for quite a long time and it is the "other" west coast paperback event that never quite lived up to the LanceCon reputation, but still proved to be an enjoyable gathering of paperback freaks and dealers. Put together by Tom Lessor in association with Black Ace books it takes place in late March every year out in Mission Hills. There Tom rents several banquet rooms and the dealers set up their tables to sell (and talke about) vintage paperback books. Here is a shot of the main dealer room:

I usually spend several hours at the show, but since we were moving the bookstore, I could only stay for just under an hour. I did find some neat books and managed to say hello to some old friends from Portland. This kind of show is a paperback lover's dream. If you are diligent, you can find all kinds of bargains. Especially towards the end of the day when dealers are willing to make deals so they don't have to take so many books home.

Now, paperback collecting and paperback cover art is a large market today. Much of this has to do with the internet, but also because the babyboomers like me wax nostalgic and want to own some of those great paperbacks they read when they were younger. The big trend now is in "sleaze" paperbacks, especially the gay and lesbian titles like:

The history of these underground sleaze paperbacks which were sold in adult bookstores and under the counter at magazine stands is only now starting to be written. Books like "Queer Pulp" by Susan Stryker and John Harrison's marvelous "Hip Pocket Sleaze" are wonderful and droll accounts of a time that seems to be strangely relevant today. And more good news; many of the classic titles are being re-issued and are pretty cheap (in more ways than one). Torreska Torres's "Women's Barracks' and Richard Amory's "Song of the Loon" are just two examples of great, classic gay and lesbian sleaze that you can buy at a hip indie bookstore or via the internet.

Still, many of the classic vintage paperback titles are still only available in expensive vintage editions that can comman prices as high as $500 and more. So you'll have to hold off on that copy of "Black Wings Has My Angel" for now (Update: just checked on abebooks.com and it looks like this rare mystery paperback original has been reprinted. Yeah!) But even with book scouts scouring the local thrift stores and mom n' pop paperback shops, you can still find good deals on some really cool books. Just check your yellow pages and look for places like "Paperback Shack", "The Paperback Trader". Maybe there's still a "Humphrey's Books" out there somewhere. Who knows?

There are many excellent on-line paperback dealers who also have open shops. Here is a short list:

Lynn Munroe Books. Lynn is probably the most knowledgeable person on the planet about paperback books. He's done more than anyone to save this part of our cultural history. He's a gentleman as well.

Kayo Books, in San Francisco, is probably the pre-eminent store for Gay and Lesbian Sleaze.

Books are Everything is one of the largest and best stores in the country.

Black Ace Books here in Los Angeles is a wonderful, unique store that has a superb collection of vintage paperbacks for sale.

And lastly, if you'd like to read more about the history of paperbacks there is no better book to begin with than "The Great American Paperback" by Richard A. Lupoff. I'm also a big fan of Geoffrey O'brien's "Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir. You can't go wrong with either book.

I've created a Flickr.com photo collection of some of my favorite covers along with additional photos of the LA Paperback Show here:

Flickr Photo Set

Welcome to the world of vintage paperbacks! Stick one in your back pocket and head on down to the local cafe for a nice hot cup of coffee and some readin. Mmmnnn mnn. -

I came to this marvelous gay curmudgeon throught the fanstasy novels of Tolkien and through the mystery novels of Ross MacDonald (Kenneth Millar). I'm one of those people who upon finding an author I enjoy reading becomes obessessed with them. I read not only everything they have writen, but often every major book written about them. In the case of W.H. Auden, I had just finished the LOTR for the second time and began looking for commentary about Tolkien and his work. I discovered that Auden was instrumental in getting the word out about how great Tolkien's work was. He wrote major reviews for each volume of the trilogy for the New York Times. He felt it was a masterpiece and explained why. I ate everyword up as if it were manna because even though I did not have an Oxford education, I felt the same way. I loved Tolkiens work as a young boy; Auden loved it as an educated man. He put me on the path to both loving and understanding Tolkien's work that has existed to the present day. I read the LOTR ever year starting in October. And I also frequently re-read Auden's essays on Tolkien as well.

I came to this marvelous gay curmudgeon throught the fanstasy novels of Tolkien and through the mystery novels of Ross MacDonald (Kenneth Millar). I'm one of those people who upon finding an author I enjoy reading becomes obessessed with them. I read not only everything they have writen, but often every major book written about them. In the case of W.H. Auden, I had just finished the LOTR for the second time and began looking for commentary about Tolkien and his work. I discovered that Auden was instrumental in getting the word out about how great Tolkien's work was. He wrote major reviews for each volume of the trilogy for the New York Times. He felt it was a masterpiece and explained why. I ate everyword up as if it were manna because even though I did not have an Oxford education, I felt the same way. I loved Tolkiens work as a young boy; Auden loved it as an educated man. He put me on the path to both loving and understanding Tolkien's work that has existed to the present day. I read the LOTR ever year starting in October. And I also frequently re-read Auden's essays on Tolkien as well.

The Ross MacDonald connection is a little more direct; I discovered Auden after devouring all of Ross MacDonald's novels I could find and then finding Auden's essay on the mystery in an anthology. Intrigued, I followed the essay and discovered that Auden was a visiting professor at the University of Michigan where Kenneth Millar (R.M.'s real name) was a graduate student. They hit it off well and since Auden was a huge fan of mysteries, he got Kenneth interested in the form because Auden felt the mystery was worthy of serious artistic expression. Kenneth went on to publish mysteries that were so good they caused usually dismissive critics to take notice. His novel "The Underground Man" was the first mystery novel to be reviewed on the front page of the New York Times by Eudora Welty. It was a great review, but I've always wished it could have been Auden who reviewed it there.

W.H. Auden is an unusual passion of mine because he's never had that patina of "greatness" for me that other artists like Robert Lowell or Robert Graves have. I've always thought of him as my very, very smart "best friend" because, like Auden, I never really acknowledged a distinction between "high" and "low" art. Krazy Kat was as "artistic" to me as "Crime and Punishment"; I am equally fascinated with "Popeye" as I am with "Princess Mononoke". Auden was a great consumer of popular culture, much like that other wonderful queen, Walt Whitman.

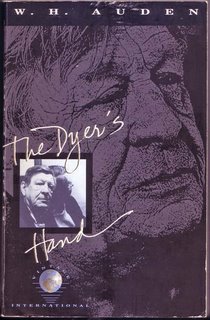

In Auden's brilliant collection of essays, "The Dyer's Hand" (1962) he makes the point that:

"The critical judgment "This book is good or bad" implies good or bad at all times, but in relation to the readers future a book is good now if it's future effect is good, and, since the future is unknown, no judgment can be made. The safest guide therefore is the naive uncritical principle of personal liking. A person at least knows one thing about his future, that however different it may be from his present, it will be his. However he may have changed he will still be himself, not somebody else. What he likes now, therefore, whether an impersonal judgment approve or disapprove, has the best chance of becoming useful to him later"

That quote was from his essay (included in "Dyer's Hand") "Making, Doing and Knowing". You can imagine how impressive this was to a 17 year old student with a love of classic literature and a secret love of heroic fantasy. In school, these subjects were never allowed to meet. With Auden, they were encouraged to meet, go out to dinner and then have wonderful sex.

No wonder Auden has been a constant in my life for over three decades.

Auden wrote in just about every field. He is probably equally regarded for his fine poetry (I love his poems about complex machines and wild woodland hills) and his criticism. If you haven't read Musee des Beaux Arts, stop reading this and go out and buy any collection of Auden's with this poem included (try the "Collected Poems"). He also wrote avant-garde plays, translations of opera, documentary film scripts and never found a crossword puzzle he didn't like. The definitive biography (for me) is the one written by Humphrey Carpenter titled "W.H. Auden: A Biography. While not a writer with high critical marks, I have admired every biography he has written (including his Tolkien biography which I've read at least 10 times). Humphrey set's Auiden's work and life in perfect contrast/unison. His homosexuality was always a part of his work, but never defined him in the way that writers like John Rechy or Jean Genet. He was gay and to hell with you if you didn't like it, he was too busy reading, smoking cigarettes, doing crosswords, drinking cheap wine, daydreaming, finding the third volume in the Maigret detective series and staring at young men. Hmnn...he does sound like John Rechy there. Perhaps I'd better re-consider my idea.

Almost every year I come back to "The Dyer's Hand". And each time I find something new to admire and think about. Listen to this from his essay "Reading":

"Good Taste is much more a matter of discrimination than of exclusion, and when good taste feels compelled to exclude, it is with regret, not with pleasure"

and this, from "Writing":

"Some writers confuse authenticity, which they ought always to aim at, with originality, which they should never bother about. There is a certain kind of person who is so dominated by the desire to be loved for himself alone that he has constantly to test those around him with tiresome behavior; what he says and does must be admired, not because it is intrinsically admirable, but because it is his remark, his act. Does this not explain a good deal of avant-garde art?"

Auden chooses, for the most part, to write in the epigrammatic style of short sentences or short paragraphs. This allows him free range to address a variety of topics within a single subject, unlike the traditional essay form with it's relentless forward motion. There are a few traditional essays in the book. "The Guilty Vicarage" is a wonderful explication and love poem for the mystery novel; "Genius & Apostle" introduced Ibsen to me as a vital and modern artist with much to say about life and happiness; "The I Without a Self" gave insight into the mind/world of Kafka that goes beyond simply reading Kafka. Listen to what he says about Kafka's readers:

"Kafka may be one of those writers who are doomed to be read by the wrong public. Those on whom their effect would be most beneficial are repelled and on those whom they most fascinate their effect may be dangerous, even harmful"

What's fascinating about this quote is that initially one is inclined to disagree, but upon reflection (especially after reading works like "Penal Colony") one see's the real truth in Auden's words.

There are other essays on the "Master-Servant" relationship in Literature (some consider this the showpiece of the book), Shakespeare, Byron's Don Juan, Marianne Moore, Robert Frost (a wonderful essay with a funny/serious ending), D.H. Lawrence. But what finally most interests me in the "Dyer's Hand" is Auden's fascination with religion and God. I am by no means a Christian, nor do I believe in God or some "supernatural" realm of existence beyond this one. But when I read Auden I become a believer for the time I am reading his essays on relegion. Somehow, the "best friend" relationship with him surfaces and I am caught up in his storytelling. I like this. It allows me to secretly "try out" spiritual thinking while I'm in his company, but then maintain my own beliefs when I'm myself again. I supose this is the storyteller's "spell" that the ancients say Homer had in spades. I guess this makes Auden my "Homer", something I have never considered until now. I like that thought.

On Critics:

"What is the function of the critic? So far as I am concerned, he can do me one or more of the following services:

1) Introduce me to authors or works of art of which I was hitherto unaware

2)Convince me that I have undervalued an author or a work because I had not read them carefully enough.

3)Show me relations between works of different ages and cultures which I could never have seen for myself because I do not know enough and never shall.

4)Give a "reading" of a work which increases my understanding of it.

5)Throw light upon the process of artistic "Making"

6) Throw light upon the relation of art to life, to science, economics, ethics, relegion, etc." -

Some of the email and comments I've received about the "Five Things" post have given me the idea that a short commentary on book buying on the internet might be helpful. Since I am essentially buying and selling via the internet (and in our open shop) every day, I am aware of the advantages and pitfalls of internet book buying. This post will try to point out some of those issues and help you make better book buying choices.

1. The majority of internet booksellers are not open bookshops, but virtual booksellers.

An "open shop" is a traditional bookstore that has an established place of business and open shelves where customers can buy/sell new or used books. A "virtual" bookseller is someone who does not have an open bookstore, but rather a space where they store their books. Their bookstore is a web-page at places like Ebay or Amazon.com. While there are many good virtual booksellers (including some who, because of rising real estate prices, used to be open shops and have become virtual booksellers in order to save on overhead, there are many, many individuals who use unethical business practices to squeeze money out of the unwary book buyer. Such practices include copying other booksellers booklistings, offering the books at higher prices (their profit on the sale) and then when they have a sale, contacts the original bookstore to pay for the item (usually asking for a "discount" in the process) and having the book "drop-shipped" (shipped to their customer).

There are many good virtual booksellers, but I tend to buy more from established open bookshops. Why? Because service is usually better, you get a wider variety of books to choose from and because you are supporting a social institution that benefits the community as well as the individual who owns the bookstore. Plus, most open shops who sell online have added a percentage to their online price in order to cover the fees they are charged by the "broker" they are using to sell their books (Amazon.com, Abebooks.com, etc). If you ask, usually the bookseller will tell you that the in-store price is cheaper and they will offer the book to you at that lower prices. Our books at Iliad Bookshop are 20% more expensive on line than in our bookshop. We routinely inform customers who order direct from us about the difference and offer to sell at the lower price. Virtual bookstores, on the other hand, have no open shop and all the prices already include the mark-up for broker fees, so you generally don't get a price break shopping at a virtual store.

2 How do you tell if a bookstore is an "open shop" or virtual?

This depends upon the business that is "brokering" the deal between you and the bookseller. In the case of Amazon.com, you have a huge amount of virtual booksellers and finding out if the seller has an open shop is often difficult. By following amazon links for the seller (including the seller ratings page) you can usually come to a link for the sellers homepage which will reveal whether the seller has an open shop. On a site like abebooks.com, each seller has a homepage that will reveal an address and contact info. Usually if the seller has a P.O. box, it means they are a virtual bookseller. Other sites may have the information easy/harder to find, but if you just take the time, you should be able determine the kind of bookseller you want to buy from.

Also, keep in mind that on sites like amazon.com, the bookseller has a rating that you can examine. I've purchased low-priced books from virtual booksellers because their rating was very high and the feedback comments were positive. Never buy a book from a seller whose rating is below 95%. You'll be asking for trouble. In fact, I never buy a book from seller's whose rating is below 98%, but that's just my own personal preference.

3. Try to buy the book directly from the bookseller

If at all possible, contact the seller directly to buy the book. As I've already mentioned, open bookstores who do internet business are set up to sell over the phone or via the internet. Some virtual booksellers do not have accounts with Visa/MC/AMX and so they rely on the broker to handle the charges for them. By contacting the seller directly you can get a possible disount and get a reasonable quote on shipping. Established booksellers usually have an honest returns policy, so if you get the wrong book, they are less likely to give you a hassle about returning it. Or, if the book is lost in the mail, you can work out a reasonable compromise in dealing with the loss. Virtual booksellers are much less likely to process returns easily or, unfortunately, with honesty.

4. Figure out your shipping options carefully.

Shipping is the one area where the internet book broker is still failing it's customers. Because no real system has been developed to handle shipping betwen the broker, the buyer and the seller, honestly, there is all kinds of price gouging going on. For example, Amazon.com charges a flat rate regardless of the size of the book. Unless we choose the size of our books carefully, our bookstore usually loses money on shipping. So, many booksellers (both open and virtual) add

some money to the cost of the book to cover those times where they lose money on shipping. In other words, these booksellers are charging you for potential loss on shipping. Understandable, but not really fair, in my opinion.

There are two basic types of domestic shipping that I think are best for books, both involve the USPO and not UPS or FedExp (which, from my experience, I do not recommend). They are "media" mail and "priority" mail. Media mail is your best bet because it's very cheap and generally reliable. A package travelling across the country will take about 7-10 days to get to you. The package that amazon.com charges you $3.50 for actually costs around $1.97 to ship, if it's a standard, 2-pound package. Priority mail is even better for those packages you want quickly. There are "flat rate" priority packs that fit books perfectly and are free at local post offices. A bookseller would pay $4.05 for a priority pack that would take about 2-3 days to arrive cross country. Larger books can use flat rate boxes for $9.90. In both cases you can expect to pay several dollars more than the actual cost for priority shipping. Check the rates carefully to make sure you are not being over-charged. Amazon.com isn't too bad, but abebooks.com allows booksellers to set their own rates and many unscrupulous booksellers will rely on the fact that many book buyers don't take the time to check what they are being charged for shipping. They offer very cheap prices for the book, but scalp you on the shipping. Still, remember that if the book you are buying is large and heavy, you'll be paying extra for the shipping. As size and weight go up, so does the shipping. You can get a good idea of what the USPS charges for shipping by going to their "domestic shipping calculator" page here:

http://postcalc.usps.gov/

Choose "package" for the size of item shipped. Put in 2 lbs for the approximate weight of the average book and then check the level of shipping you want. This is a good way to understand the range of shipping options you have and their relative costs.

International shipping is even more problematic than domestic shipping. Since foreign shippers will be using their own postal system for shipping, there's no way to tell what a fair rate would be. You'll have to do some comparison shopping here to get an idea of what a reasonable shipping rate would be. The first thing to do is to contact the seller and request a shipping quote for both surface and air shipping. Any decent seller will offer this information. If they refuse, do not buy from them period.

Surface mail is the slowest and most unreliable method of international shipping. You package travels by boat and is usually stored in huge bunches on pallets in the ships hold. Needless to say, the handling is terrible and your package might get damaged. Airmail is the best method. Many countries have a flat rate airmail rate that can be a cost saver if the bookseller is honest. Ask about this when you inquire about shipping. Remember though, there is usually a weight threshold where the price starts to increase dramatically. In the U.S. that pound limit is 4 lbs. So, don't be suprised if your large book shipped via airmail from Germany is very expensive.

5. Don't be afraid to ask questions, but ask intelligent ones

Always ask about something you don't understand when you are purchasing a book. While some obvious questions are tedious to answer over and over, I really don't mind telling you that I will pack and ship your book carefully. In fact, I probably pack these shipments even better because I want to make sure they get their book in the best condition. While I generally pack books in jiffy bags, I'll box it if the customer makes the request. It's also important to ask about the bookseller's return policy if the book is damaged. Some will not return you book or refund you unless you have purchase insurance. The USPS has very good insurance rates and you should be able to get insurance for a regular sized, average books for only a few bucks. ALWAYS insure your expensive purchases. UPS and FedExp have a slight advantage here because insurance and tracking are automatic with these carriers. But I think the terrible customer service these huge corporate dumbells provide offsets their benefits in this area. That is why we choose not to use these companies for shipping.

Tracking your package is another big issue with books. Many customers assume that packages are trackable and routinely call us and ask for a tracking number. The USPS does not provide tracking unless you pay for it. We spend a little bit more on our shipping to get delivery confirmation so that when a dispute arrives we can verify if the package was delivered or not. Personally, I don't need tracking info on a package so I don't ask for it. Each internet book broker has different polices regarding tracking. You'll need to read up on them in order to know what you can or cannot do.

6. The lowest price is not always the best price for a book.

The internet is a book buyers market. While sellers make money, a book buyer has the advantage of being able to search hundreds of sites for the best price. Many sellers routinely underprice books in order to move them out of their store. I almost always research the books I catalogue for sale on the internet and underprice all of the other sellers on Abebooks.com because we bought the book cheaply and I want to sell it cheaply. This is another advantage in using an open shop bookstore to buy books from: you'll almost always get a book in the condition it is described in. I only buy books in good condition and when I describe the condition of the book on the internet, I over grade it. That is, if the book is Fine condition, I list it as "Very Good", etc.. This results in happy customers.

When you see a book online for forty cents and then another one for $4.50, you might think that the forty cent book is the one to buy. But this isn't always the case. On amazon.com check the sellers rating. Sure they sell cheaply, but they often ship very late and package poorly. Also, you might be getting a book in very poor condition, even though it's described as "in good shape". Underlining, highlighting, torn pages, are all underscribed in very cheap books. Since they are selling their books so cheaply, they want to spend the least amount of time in processing the book. This includes the book description. That $4.50 book might be the best one to buy because it's coming from a legitimate booksller with a high bookseller rating and because it will arrive in a timely manner in the same condition it was described.

I hope these comments have helped you understand better how to buy books on the internet. Please leave any questions you may have regarding this topic and I'll answer them as best I can.

And now here is a short list of internet sites and brokers you can use to look for that special book.

The best book search engine is:

Addall.com

this is a meta search engine that covers almost all of the major sites including abebooks.com, alibris.com, amazon.com, powellsbooks.com, etc. The advantage with this site is that you can comparison shop with different book brokers to get the best price.

The three best book brokers on the net:

Abebooks.com

Alibris.com

Amazon.com

Each of these book brokers have advantages and disadvantages that you'll have to weigh before you use them. On balance, abebooks.com is the best, in my opinion, because of direct access to the bookseller. But their shipping matrix is poor, whereas Alibris.com has an excellent shipping system. Amazon is an excellent site for more contemporary books. Pricing is all over the map on collectable books, so you'll have to do some searching using addall.com to find the best price.

Three outstand bookstore with major net presence:

Powell's Books

King's Books

Tattered Cover Books

Strand Bookshop

and, of course, The Iliad Bookshop

Powell's books, in particular, is an outstanding online bookstore. I highly recommend them, even though their huge size sometimes leaves for occasional inconsistent customer service, they have one of the best collections of used books in the world. -

Over the years, I've noticed that there are certain myths or misconceptions that people have when they are selling their books to a bookseller. After conferring with my partner, Lisa Morton, we've come up with five of the most common ones. In fact, just yesterday someone on the phone used one of them. In the interests of the mental health of booksellers, please read this list and the next time you are selling books ask yourself if your comment is on the list.

1. It's a really old book, so it must be worth a lot of money, right?

-We probably hear this one more than any other, which is why it is number one. It's not the age of a book that determines it's value, but it's rarity. A book can be published 100 years ago and not be as valuable as a book published a year ago. Why? Because one is more rare than the other. If you publish tens of thousands of copies of the 100 year old book and only 100 of the year old book, the former will be more rare. Old is usually defined as "antique" or around 100 years old. Rare means "scarce" or "few copies in existence". One of the rarist of books is the first printing of "The Good Earth" in paperback in the U.S. Out of a print run of about 100,000 there are only 5 known copies in existence with the original dust jacked (yes, some early paperbacks had dust jackets). So, just because the book is old doesn't mean it is valuable.

2. But, I'm positive this book is a first edition.

-this misunderstanding is more foregivable because sometimes the book will actually say it's a "first edition". Of course, the same book can also say "book club edition' as well. And when we point this out, the person will invariably say, "It's a first edition of the book club edition". Nope. Sorry. Book clubs are reprint edition. It says first edition because the book club publisher used the same plates to print the book. Determining whether a book is a first edition is not always easy. Especially for books printed before WWII. In the last several decades book publishers have started to use a relatively uniform system to identify the edition of a book they have published, however, before WWII each publisher determined their own method of identifying editions. Some stated first edition, some did not, but identified reprints. Some had no information at all. There is a large book devoted to all of these publishers criteria. It is called "First Editions, a Guide to Identification" by Edward Zempel and Linda Verkler. We use it frequently at the bookstore. But even then, some books are notorious for lack of information. I think there is a Faulkner first where you have to turn to a certain page and if a sentence has a word misspelled its a first.

3. Why can't you tell me what it's worth over the phone?

- this one is just stupid. How many times have I ventured a guess at a price over the phone only to find that when the customer brings the book in it's a) not a first edition and b) not the condition they described (see number 5 below). And when I tell them that the book is not worth anything, or only a fraction of the price I quoted, they say, "But you told me it was worth $. I've learned never to quote over the phone because people always tell you what they imagine the book is and not what it really is. Plus, it's just not good business.

4. I looked the book up on the internet and it's worth a lot of money

- the book you found on the internet is not the book you have in your hand. Or, if it is the condition is not the same. Your book is falling apart, missing a dust-jacket and is not a first edition. The book listed is in fine condition, has a dust jacket and is a first. Books are unique. You have to know something about them and how to identify them in order to be sure that the book being quoted at a book site on the net is the same as the one in your hand. Interestingly, you can learn most of this in about an hour of study at the library. Look for "Book Collecting: a Comprehensive Guide" by Allen Ahear (referred to as the "Ahearn" in the book business). Aside from being just a well-researched, well-written book, there is a complete introduction on how to identify firsts, grading condition of books and a general introduction to book buying. Plus, there is a list of famous books and their relative values. This book is updated every year, so be sure to look for the current version (2005). You can also go to our website for a basic intro. Knowing this kind of information will save you plenty of time when you try to sell your books at a used bookstore. Plus, it's just interesting stuff.

5. Oh, yes, the book is in perfect condition.

-the second most common phrase we hear. Of course, the book is not in that condition when they bring it in. It's covered with silverfish, cobwebs, the pages are loose, no dust jacket, the corners are bumped and the color plates are missing, but otherwise it's in pefect condition. There three grades of book condition. 1-Fine - the book is in perfect condition. no flaws. 2. Very Good - slight problems, minor scuffing, etc., 3- Good - major flaws, but still readable. 4-Fair - book is in very bad shape, but still readable. There are sites on the net where you can get good descriptions of each condition. heres one: Link

A general rule about selling books expect to get about a quarter to a half of what the bookseller is going to sell the book for, not what the price is on the dust jacket of the book. Some books are more valuable to differnet booksellers. If you have a valuable book, it pays to shop the book around (not by phone, see number 4 above). There are certain books that we put on our 2 dollar table even though they are more valuable at other stores. It all depends upon each stores buying practicies and store theme.

Lastly, books are unique, but some books are more unique than others. It's these books that demand a high price because you can't find them easily and because the information they have is unique and unusual. Common books (usually best sellers) are not worth much to re-sell because there are so many of them out there.

Selling your books to a used bookstore doesn't have to be a mystifying experience. Most problems are due to ignorance and high-expectations. If you do some homework on your books before you sell them, you will have a better idea of what they are worth. And you can always call the bookstore you are going to sell to and ask them what kind of books they are buying. Better yet, go there and take a look at the books on their shelves. Fifteen minutes of browsing will give you a good idea of what kind of books the store is going to buy.

Additional Links:

http://www.ioba.org/desc.html

Iliad Bookshop Book Grading

Guide to Identifying First Editions -

Comic books were an enormous influence on me as a young boy. I was a Marvel Comic's kid and right at the time I needed to understand how to deal with the world around me Peter Parker and Ben Grimm were dealing with the same issues. Since my narcissitic parents paid little attention to their responsibilites of raising a child, I was left to find my answers in the pages of Fantastic Four, Dr. Strange and Spider Man (to name a few). My feelings of guilt, anger and confusion were what Marvel comics characters were dealing with as well. They were my daily companions and advisors. Plus, they got to save the world, which was a wonderful fantasy for me. Even Stan Lee's "nuff said" gruff style became my personal tick that probably annoyed the hell out of my schoolmates. Comic characters were my friends in ways that real people couldn't be. The entrance of Galactus in the Fantastic Four made me worry for the safety of the Silver Surfer for days. It was like my own father intruding on the pages of my private world. This was my first inkling of something called the "Epic" style. And like the great poet and essayist, W.H. Auden, who had no distinction between "high" and "low" art, I am still influenced today by those brilliant images and stories. Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby are as much a part of my imagination as Dore and Edward Hopper.

All of this is by way of introducing what has taken the place of comics for me now that I am fifty: graphic novels. As I grew older, college and theater became my obsessions and I was content to pick up the occasional comic, but I just couldn't find them as interesting now that I was an adult. Chekov and Kafka had edged out Thor and the Dread Dormammu. All of that changed when I read an excerpt from "Maus" in Raw Magazine. I was so impresseed that I went right out and bought this new "graphic novel" and spent the rest of the day immersed in this strange and beautiful world. I didn't know it at the time, but "Maus" was the first masterpiece of a form I have come to love in the same way as I did comics: the graphic novel. And I have been reading them with hunger for the last 10 years. We are in a renaissance of sorts for the graphic novel. I'd like to review two recent examples of the form that I think are wonderful.

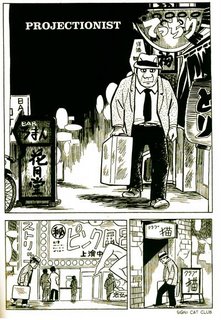

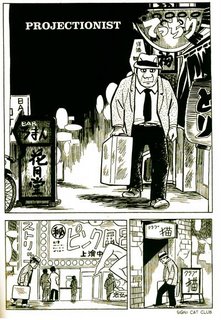

Yoshihiro Tatsumi is the grandfather of Japanese underground comics. He started writing and drawing more adult themed stores as far back as the 1950's when most of the manga art of the time was garish and overblown. According to the excellent introduction by Adrian Tomine (himself a great graphic novelist), Mr. Tatsumi is a prolific artist who currently runs a bookstore and continues to create short illustrated stories that reflect his ambivalence about people and modern life. Amazingly, "The Push Man and Other Stories" is the first official English language collection to appear in the States. The 16 stories that make up this brilliant collection were all composed around 1969, but you wouldn't know it from this simplicity of his writing. Instead of aliens and monsters fighting high school kids, we have everyday people trying to make sense of their dead-end jobs and their philandering lovers. The "Push Man" of the title story is a young man who "pushes" the crowd into a packed subway car. His sexual fantasies of "pushing" young women are realized by a woman who, after getting drunk and having sex with the young man, invites her girlfriends over to "push back". In the end the young man is pushed into his own subway car and can't get out. The slightly cartoonish characters set against a highly realistic background are mesmerizing. Each panel is a small work of art that pulls you in to a world of hope and despair; boredom and violence.

Reading "Projectionist" is stomach-turning, but not because of anything that is shown on the page, but for what the story suggests is being seen. The projectionist of the story charges high class businessmen and their call-girls for an evening of "special" pornography that both disgust and arouse the viewers, but leave the projectionist unmoved. His loneliness and despair are depicted in the brilliant panels of him walking through cities in the cold wind with his briefcase full of hellsex in hand. The careful detail in creating the man's facial expressions lend pathos to the suprise and ironic ending. In fact, in reading the stories I'm struck over and over again with the variety and beauty of Mr. Tatsumi's characters. They behave in suprising and shocking ways; sudden violence or cruelty coming from repressed rage and desire; quiet desperation and an endless desire for some sort of connection to another human being. Sex is a major element in all of his stories. But it doesn't seem to appease the deeper longing inside of his characters. These are urban horror stories are told with the simplicity of Raymond Carver, but with the twist of a writer like David Lynch or Jonathan Carroll. The art of the graphic novel has never been more obvious than with this collection of stories by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, a writer I hope you will read. Fortunately, Mr. Toumine is hoping to bring out a whole series of this writer's works beginning with he present volume. Drawn & Quarterly, a Canadian publisher distributed in the U.S. by Farrar, Strauss, is to be contragulated for publishing this wonderful book and for desiging and edition that the author would be proud of. Let's hope this book is successful enough to continue the series.

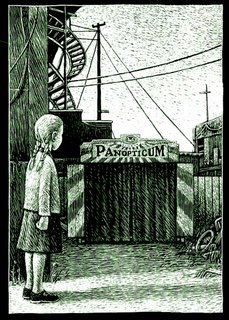

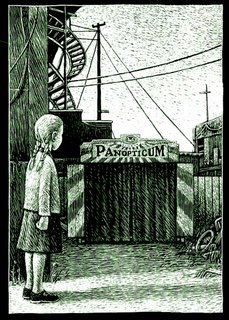

Thomas Ott is another amazing cartoonist that has caught my eye recently. "Cinema Panopticum" is a completely wordless collection of stories all organized around a young girl who visits the Carnival, but doesn't have enough money to enjoy the rides or any of the booths. She is very sad as she starts to leave the park, but tucked away in the corner is a small tent with the words "Panopticum" on a sign over the entrance. She enters and finds 5 old-fashioned movie viewers with titles like "The Experiment" and "The Hotel" written above them. To her delight, she finds that she has just enough money to use all of the "panopticum viewers". Each movie she views is told as a seperate story in Ott's book. The little girls view becomes ours.

While Thomas Ott is not as subtle an artist as Tatsumi, his visual style and attention to detail is superb. Using a high contrast Black & White palette, carefully scratches each sliver of his characters so exactly that it is a marvel to behold. And this almost overly detailed style matches pefectly with the strange, supernatural themes of his stories. The detail makes the gruesome morbidness of his world seem real and believable. His characters are unusual and, at times, grotesque. Much like the garish world of the Carnival itself. In one panopticum story, "The Champion", a mexican wrestler has to wrestle with death himself when there is a prophecy of death in his family. Of course, there is a twist ending which the young girl in the Panopticum tent finds astonishing (and so do we). Antother story features a homeless man who discovers that the "end is near" and attempts to tell everyone. But no one listens and the world is destroyed. My favorite story is the last one called "The Little Girl". You can imagine how our young girl responds to it. The last panel of this wonderful graphic novel is of the young girls leg disappearing as she runs in terror fromt he tent.

There is certainly a good deal of horror fiction in Thomas Ott's writing, along with Twilight Zone and Stephen King, but Ott's style is so uniquely his own that he gives new life to old themes. Mr. Ott is Swiss and is the lead singer in the band called "The Playboys". Fantagraphics is publishing his work in America in beautiful hardcover editions with illustrated boards. This publisher seems to be at the fore-front of the graphic novel movement. A quick look at their website and you'll see many outstanding artists represented. I've begun to collect Thomas Ott. He's a remarkable artist who, in addition to his graphic novels and stories, also does political cartoons and cartoons for several newspapers.

If you have never read a graphic novel, now is the time to go out and buy one. We are in a highly creative era of this art form. Along with the two artists I have reviewed here, let me suggest a few others for you to consider.

The Black Hole by Charles Burns (The single best graphic novel I have ever read!)

The Watchmen by Alan Miller

Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron by Daniel Clowes

Maus by Art Spiegelman

Berlin: City of Stones by Jason Lutes

Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer: The Beauty Supply District by Ben Katchor (and you thought "Death of a Salesman" was a good story? This graphic novel kicks it's ass) -

Say hello to our new store cat: Zola! Since our previous store cats find it hard to travel from their home to our new bookstore location, we have been on the look-out for a live-in kitty to guard our store every night and to keep an eye out for book mice. Our friend, Christa Faust, works with animal rescue here in the Valley and she told us about a one-eyed cat she rescued from an abusive situation. We very much wanted to meet this cat and one day Christa brought her to the store (her vet is in the neighborhood) and everyone instantly fell in love with "Zola" (including all of the customers in the store at that time). It tooks some time to convince Dan, the owner of our store, that we needed a new store cat, but Lisa and I worked our special juju and just last week Christa brought Zola to stay for good.

In the picture you can see her licking her chops from all of the special food we are giving her to fatten this little kitty up! She's about 2 years old and still has a tremor in her leg from the mistreatment she received, but she loves to play and is very affectionate to everyone who comes into the store. She's been at the Iliad for about a week now and has her own bed and play toys. She runs and runs down the long open stretch that goes down the middle of the store. Then in the afternoon she sleeps it off.

We are so happy to have Zola with us. In spite of the abuse she has received, she's not shy at all. She's so curious and full of fun. I just love her. I call her "Zo".

Isn't she wonderful! -

So sorry for the lack of posts here recently, I've been up to my ears reviewing a new 3d animation software called IClone. You see, I've been involved in something called "machinima" (machine + cinema) for the last few years. Machinima is a kind-of poor man's Pixar animation. We can't afford the cost of creating top of the line 3d animation like "Shrek" and so we use PC Games as our tools and shoot our movies inside of the games. It's got an underground following that's slowly breaking out into the mainstream with shows like the History channel using the PC game "Rome" to illustrate a documentary on famous battles. MTV has been using machinima to do all kinds of spots. The game companies are starting to get behind this form of filmmaking by providing all kinds of free tools to create films inside of their games. And one game in particular (The Movies) has as part of playing the game, the ability to create your own films.

Anyway, I've been doing mostly sound and acting for several films over the last year. When the opportunity to review this new software came up, I jumped on it. I've spent the better part of the last month learning the software and creating three short films as part of the learning process. I think that you can best understand how a creative tool works by actually creating something with it. That way when you are in the middle of production you can easily see what works and what doesn't with the program. IClone is basically a beginner's program for 3d animation and modelling. And it's pretty good, too.

So what does this have to do with books? Well, I decided to try the sister program to IClone which is called "Crazy Talk". This program let's you animate in 3d any digital image. So, when I was looking around for something to animate, I happen to look at a recent vintage paperback I'd picked up called "Hell Cat". There was a juicy picture of a femme-fatale on the cover. It suddenly occured to me that I could animate the face of the woman and have speak a sentence or two of dialogue. After a week or so of experimenting, I actually created a short film showing this animated cover. I also found several B&W pictures of mobsters in a Mafia history book that was in the free box at the Iliad Bookshop and animated one of them as well.

What's so interesting about both of these programs is that they stimulate my imagination and give me ideas about how to use book covers and book illustrations as sources for characters and backgrounds in machinima filmmaking. Imagine taking a Durer drawing and using it as the basis for a short film; or a Schiele painting; or an old Children's illustrated tale. Stitching the illustrations together and adding dialogue or sound effects would be a fascinating experiment. All of this is possible for a beginner like me using these two programs.

Here are the two short films I created to accompany my IClone review:

Hell Cat

The Mobster

and the final short film I created with IClone is here:

The Skip Heller Show

If you are interested in learning more about machinima head over to this site:

Machinima Premiere

Some recent IClone films can be seen here:

You Tube Iclone -

This is the kind of day where I appreciate the Calendar section of the LA Times. Instead of the usual speculation as to why the movie box office is slumping, there was a well-written article on Grove Press's new 5-volume Centenary Editon of Samuel Beckett's works. Tim Rutten, a times staff writer I'd like to read more of, wrote a perceptive and helpful article on the edition that actually includes comments on the design of the books; something usually left out of many book reviews. He points out that the edition is not the complete works, but it contains everything that is essential in Beckett's works. With the possible exception of his novel "Watt", I think he's right.

The overall series editor is Paul Auster, but each volume has it's own seperate editor. The first two volumes cover the novels and are edited by Coim Toibin and Salman Rushdie. The Grove/Atlantic website doesn't list the contents, but I sure hope it includes Beckett's first novel, Murphy, which is an absolute knee-slapper he wrote while starving in London. To stay warm, he'd hang out in the movie theatres and was especially enamoured of Buster Keaton. You could probably say that Murphy was an extended fantasy of Beckett's where he imagines himself as a kind of Keaton character pulled off of the screen and given Beckett's troubles. I recommend this novel all the time to people at the bookstore and they come back raving about how good it is. In many ways (and as Tim Rutten points out), Beckett was a master of the novel as well as of the stage. I'd go further and say that he was a better novelist. The novel allows Beckett to speak directly to the reader, whereas his plays have to be understood through the medium of the actors, directors and designers who produce it. The novels (with the exception of Watt) are so well-written and bittersweet that I found myself enjoying them more than the various performances of the plays I'd seen. Beckett always wrote for himself. Watching his plays in the theatre (especially a good production) I've grown frustrated with the audiences who inevitably end up laughing and tittering because they can't quite figure out what's going on when it's perfectly obvious. Reading the novels you have the luxury of losing a dull audience and listening to Beckett directly. I'm a snob, but it's the truth.

The other three volumes are; Vol. 3, Dramatic works (Edited by Edward Albee); Vol. 4, Poems, Short Fiction and Criticism (Edited by J. M. Coetze); Vol 5, "Waiting for Godot" (bilingual edition, but no editor listed). Albee is not my first choice for editing the dramatic works. Pinter would have been better since he had an ongoing relationship with Beckett and used to submit the manuscript for all of his plays to Beckett who would make comments in a red pencil. I wonder if Pinter was asked to do the editing, but because of ill health, declined. Coetze is a wonderful choice for the short fiction, poetry and essays. I've long admired his work and look forward to reading his introductory essay.

Norman Dubie, the great unknown American Poet, once taught a class at Arizona State and I took it. He was a nut, but a brilliant nut. During an office visit, I asked him about Samuel Beckett and he told me that Beckett scared him. When I asked him why he said, "death, death, death...I won't be able to understand him until I'm an old man". Well, that's probably true for Mr. Dubie, but I started reading Beckett in my teens. I'm reasonably sure I understand him (although the novel Watt is still a puzzler), but perhaps a deeper understanding will come when I'm in my sixties.On second thought, no, I don't think so. I'm going to buy this new set and read him all over again. Beckett is the most important writer of the 20the century. This set is a perfect way to discover him, or, re-discover as the case may be.

PS I went into the camp of the enemy and snuck a peek at the new editions (which are all on the shelves) and the design is, well...good. No dust-jacket, but with an embossed image on dark blue covers. It looks rather like a school book. Beckett would have liked that, I think. The font and layout are very nice. These books will be easy to read. What I don't get is why the colors are so muted. This seems to be the cliche notion of Beckett as somber and grim. Where the truth is: he is somber and grim, but he's also damn funny, strange and marvelous. There is no sense of fun in this design, whereas there is an enormous sense of fun in Beckett's works.

Quick note on the novel "Watt": Beckett wrote this novel during the occupation (as I recall from Deidre Bair's bio of Beckett - still the best, in my opinion and to hell with amazon.com reviewers) to try to keep himself sane in an insane time. The books style and content reflect this preoccupation with detail. It's an amazing, unreadable book that reads like the journal of a mental patient trying to describe his/her daily life. At one point in the book the narrator comes into the master's bedroom and for almost four pages he describes the various ways the furniture could be re-arranged; all in puns. For example, the headboard could be placed on it's back while the sideboard could be placed on it's head....(get the idea?). I suppose it should be included in his selected works, but be warned reader; you venture onto thorny ground. Even the title is a joke: What? Watt?

-

Amazingly, we have gotten the stolen "Men Without Women" first edition back, slightly damaged, but with a $100 tucked in the book to pay for the damage. I'm still reeling from the chain of events of the last two days.

Here is what happened;

Friday, Gloria and Lisa both had the idea that we should look on Ebay to see if anyone might be trying to sell the stolen first edition of "Men Withought Women" by Ernest Hemingway that I mention was stolen on Iliad Bookshop's opening day. Sure enough, there was a copy up at a starting bid of $1,499 with a description that almost matched our ABE (advanced book exchange) description where we had the book for sale. Only a few small words were changed. When we looked closely at the picture that accompanied the auction, we realized it was the same picture we used at ABE only cropped and brightened up, probably in Photoshop. After checking the seller (who was located in Texas), I remembered that one of the men who spent time in the rare book section where the Hemingway was located, mentioned he was from out of town and would be leaving in a day or two.

We decided to file a police report and then contact Ebay. We should have already filed a report, but that's another story. Dan was all for contacting the person on Ebay directly with a basic statement that we know the book was stolen from our store, we have a witness (which wasn't really true) and that if he didn't return the book, we'd contact the FBI. Dan also worded it so that if the book was returned there'd be no questions asked.

Both Lisa and I thought this was tipping our hand too soon, but Dan had had experiences with the police before and was not confident that they'd do anything. Lisa sent the carefully worded statement to the person on Ebay and I wrote out a statement for Dan to take to the police tomorrow.

At around 9pm this evening Dan called us at home to tell us that he had the Hemingway back in his possession. He told us that someone had called the bookstore and told him to go out to the postal box on the side of our building and look inside. The person apparently hung up before Dan could say anything else. Dan went outside and, incredibly, the "Men Without Women" copy was inside, along with a $100 bill and a short note indicating the money was to cover the cost of the damage to the dust jacket (there was a small tear on the rear cover that wasn't there before).

When Dan called us, we immediately checked the Ebay auction and it was still up for sale. However, I've just paused in writing..(there it was)...and the auction has been removed. Isn't this the strangest turn of events? Apparently, there must have been two people; one was the person with the book here in Los Angeles, and another with the Ebay auction in Texas. The Los Angeles person must have had a change of heart when he was contacted by the Texas person and decided to return the book. Ebay may have contacted him at the same time our email arrived. Dan was right: the best approach was a direct one.

I had suspected that the theft was one of opportunity. The "my God, no one is looking, I could steel this book" kind of thing that could tempt just about anyone. This person just succumbed to the temptation. They must have been carrying a load of guilt to return the book so soon after our contacting him. It's also possible that the threat implied in Dan's email may have simply scared him. I'm voting for the first explanation, since the person left a $100 bill in the book as well as returning it. All I can say is, "Thank you for returning the book. You did the right thing!"

So, now our store opening was a complete success and, incredible as it seems, we had a $4,000 book returned by the person who stole it.

Yay! Oh, Frabjus Day!

-

A little over two weeks ago, the Iliad Bookshop (where I work) began moving its 100,000+ stock of books to a new location about a mile away. I worked for 131 hours alongside volunteers and co-workers to get the new store opened by April 1st. Today, I am writing to you having survived the Great Iliad Bookshop Migration. We managed to get all of the books, the store fixtures, the bookshelves, supplies, statues, plants, files, computers, lumber, couches, coffee tables, rugs, posters, signs and front counters to the new store and arrange them so we could open this last Saturday, April 1st. Of course, we were all exhausted and bruised, but we opened the new doors to a rush of people and did booming business all day Saturday. I've finally managed to get enough sleep to sit down and write about it. I've also created a Flickr.com account that has about 3 dozen photographs arranged chronologically, so you can get a visual idea of what it was like. This event was probably one of the hardest things I've ever done physically. I was worried about my back most of all, but despite a day that was touch and go, I came through it weakened, but proud of what we had accomplished. What follows is a short description of how we went about moving an entire bookstore.

But first a little background: The Iliad Bookshop had been at the same location for over 18 years. The reason we decided to move was because our landlord (Lord Voldemort) decided to take advantage of the crazy real estate market in California and at the end of our recent five year lease decided to raise our rent over 70%. This was the final straw for our owner, Dan, who has had to deal with the impecunities of Lord Voldemort for years and years. Dan went out and found a building that was the right size and a good location (and with room to grow) and be bought it. The financing took a long time to get put into place, so we were delayed in moving and ended up having only two weeks to move the entire store.

After talking over the logistics a bit, we bought 1,200 book boxes from a local box store. Dan went to the new store location and began to break down walls and get the space ready for the parquet floor he was going to put in. The new location is 8,000 square feet, but the space we were moving into is only 3,000 sqft. There are two other businesses who occupy the additional 5,000 sqft. When their leases expire in the next couple years, we will take over the space and expand our new store to triple its size. This was one of the things that made the building so attractive. But for the present, we had to break down what was an old television studio, put up a new wall and get the floors ready to be covered. Dan took about a month to get the job done, a frustrating job since we discovered all kinds of problems with the electrical, plumbing and support beams in the building that had to be fixed before we could move in. Dan was working 12 to 16 hour days long before we even began to move the store. I don't know how he did it.

Back at the old store, we had spent several months weeding out books we didn't want to move by putting them in the various free boxes out in front of the store and by culling the stock for our sale tables. This involved going through every section in the store and pulling books that had been there for years and re-pricing them to the sale tables. After storing the huge pallets of flat, empty boxes in our back rooms, I began to label every shelf in the store with a number system that would enable us to re-shelve the books in the new store in alphabetical order. In some of the pictures you'll see yellow post-it notes with numbers on them. These were the numbers that were copied to the boxes when they were packed so we could know what books were inside each box. In general, this system worked well and we were able to re-shelve efficiently. However, a problem we did not foresee was that some sections did not go into the same bookcases, since Dan had to mix and match at the new store to fit the space. Of course, the Art section was one of these and I spent most of a very tiring day with volunteer Dave sorting through every single book (Dave ended up doing most of the section and told me he never wanted to handle a book by Picasso every again).

We began packing on March 16th. Fortunately, we had almost 10 volunteers (to whom we gave bookstore credit for hours worked) who dove right in and got us off to a fine start. We moved all of the paperbacks first and managed to get everything packed in one day, along with most of the shelving (we moved the empty bookcases whole). I think we packed and moved something like 30,000 paperbacks in one day. Bob, the king of paperbacks, and Dan went to work at the new store and got the first rows of shelving up and we began to re-shelve the next day.

Slowly, very slowly, we began to work through each section in the store. We reserved the paperback room, which was cleared now, as the storage room for the new boxes as they were packed. Stupidly, I didn't pay attention and group all of the boxes by sections in the first few days, so many subject sections got mixed up (something that made for a lot of extra work sorting them out at the new store). Once I realized my mistake, we got the sections together and it was much easier to reshelve at the new store. The pattern became: packing books at the old store, loading up the big rented truck with about 100 boxes stacked three high (they fit perfectly on to a hand truck this way), move them to the new store and dump them in a clear area. We did this pretty much strait through the first week until we had about half of the books out of the old store.

Then we ran into a snag; Dan wasn't able to get new shelves up fast enough for us to put books on them. So, we all had to go to the new store and shelve like crazy while Dan worked on getting the shelved together. At first I didn't realize why Dan was slow, but then I remembered he had to cut off the top shelf of every bookcase because the ceiling at the new store was 2 feet lower than the one at the old store. That and the fact that many of the shelves had to be re-backed and braced together, slowed our boxing and moving for several days.

Lisa drove the 16 foot, 6-wheeler truck with a liftgate every day and she did a great job. We kept joking about her being the "Large Marge" character from the Pee Wee film. You can see her in the photo-set looking tough behind the wheel. Backing into the backdoor's of each store was a real bear and there were some nail-biting moments, but Lisa got the hang of it and eventually it became a piece of cake, except for the

"DAY FROM HELL".

.....The Day From Hell.....

Let me tell you about the "DAY FROM HELL". Dan managed to catch up with us and we were able to go back to the bookstore to pack the the last sections. We were making good progress when it started to rain. The volunteers had thinned out and we only had two left (thank you, JB and Dave!) and we had to get about 500 boxes of books to the new store in the rain. We managed to park the truck close to the back door and rig a kind of tent to keep most of the rain off of the books, but as the day progressed all of the floors got wet and there was water everywhere (I was soaked all day). On top of that we were moving the heaviest boxes, the Art books, some of which weighed up to 60lbs each. I had a terrible scare when the end of my shoe got caught between the liftgate of the truck and the edge of the truck bed. The liftgate operator wasn't paying attention and I stared in horror as the end of my shoe got crushed. Thank God, I wore shoes that I had bought from the Thrift store and that were slightly too large for me, because there was lots of space at the end of the shoe and the liftgate just missed my toe. I had dodged a bullet that time. I continued on as if nothing had happened. It was only later, in bed, that I realized how close I had come to disaster. Another awful moment in the "DAY FROM HELL".

By this time we had made three trips and came back for a fourth when some guy came into the store and claimed that our truck had hit his car. After looking at his car (which looked like it had been hit by someone), listening to his contradictory story, and looking at our truck (which had no marks on it whatsoever), we told him we didn't think we hit him. He started arguing with us and blah blah blah. Well, this went round and round for an hour while most of us kept on loading up boxes. Eventually, Dan came over and we exchanged driver information and decided to leave it to the insurance company to sort out. Lisa was upset and didn't want to drive the truck for the rest of the day. We managed to get one last load during very heavy rain, over to the new store where we were all so tired we were just going to leave the books in the truck and unload them the next day. But Dan was worried the truck might leak, so (all of us groaning simultaneously) we unloaded the heavy, heavy, wet boxes. I think we went home at around 8pm after a 10-hour day lifting boxes. Thankfully, that was the ..

.....end of the "DAY FROM HELL".....The next day was much better (apparently, Librus, the Greek god of books, decided to spare us this day) and we managed to speed up our loading and get some more volunteer help. Moving the large fixtures (the front counter and the sale tables) turned out to be much easier than we thought it was going to be and we got them all loaded and moved in one day. By the 10th, however, my back started to give me trouble and I had to stop frequently to rest. I think all of us paced ourselves very well for this huge job. Every night I'd have a hot bath to sooth my muscles and I'd take a Motrin twice a day for pain. Our volunteer, JB, was a demon with work though. Man, this guy would stay for another three hours after Lisa and I would leave! I asked him where he got the energy and he just smiled at me mumbling something about energy drinks. Lisa tells me that he told her he drank a concoction of orange juice, mountain dew and coke every morning. He called it his "jet fuel".

Despite the wear on our bodies of moving almost 4,000 boxes of books, we got everything out of the old store. The weather cleared and we spent most of the last few days shelving and cleaning the new store for last Saturday's opening. Dan found that he had run out of shelving and so we weren't able to get Science, Nature, Erotica, Counter Culture, Cookbooks and a few other sections up onto shelves. But we got about 90% and when the doors opened people were very pleased. Of course, one of the first customers asked for the Cookbook section and I had to give her the sad news that all of the books were still in boxes (she didn't like that sound of that from the sour look she gave me). Dan plans to get the new shelves up within a week or two. He makes them from scratch; stains and waxes them so they look very nice.

We were not without some problems, however; several sections had very curious alphabetization and some books were in completely the wrong sections. We also lost our two large couches (no room) which was disappointing to some customers. We plan on adding chairs to make up for some of the loss of comfort. We also had big problems with SBC over our DSL line. Eventually, we just fired them after one bureaucratic foul-up after another. Our Credit Card terminal had to be upgraded which took many calls on the phone late into the night. But the opening went very well. The store, while not complete, looks beautiful. The parquet floors are simply wonderful. Gloria is almost through with her magic bathroom. My friend Skip, the jazz guitar genius, remarked that he had played on stages that were smaller than our bathroom. I love it. If you make it to 5400 Cahuenga in North Hollywood, you must use our new bathroom and tre cool toilet. Our plumber, Jason, told us, "I love this toilet". Oh, and the great books.

The only real downer for the whole experience was the theft of a very expensive Hemingway first edition from our rare bookshelves on opening day. We separated all of the rare books, but weren't able to get everything behind glass and locked. Someone took advantage of this and slipped away with a $4,000 book. We were all depressed about it for a day or two; and we're taking extra precautions now, so it won't happen again.

So, that's the story of the Great Iliad Bookshop Migration. We are slowly getting back into shape. The store looks wonderful. We are buying books again and the rhythms of our store are starting to become familiar again. I'm heaving a big sigh.....Aaaaahhhhhhhhhh.......

Thanks to Janet, Dave, JB, and all of the others for your help. We could not have gotten our store moved without your help. And thank you, Dan and Gloria, for having the courage to take such a huge risk and for all of your hours of hard work. I'm proud to work for you. And thanks to Loki, for making it fun to work (stop biting my shoes...down, Loki, down!)

If you happen to be in Los Angeles, come on by our new bookstore in North Hollywood. Loki would like to see your shoes and I'd like to show you around our new store.

Iliad Bookshop

5400 Cahuenga

North Hollywood, CA. 91601818-509-2665Mon-Sat, 10am to 10pm; Sun, 12pm to 6pm

-

"The Zapruder Film: Reframing JFK's Assassination"

by David R. Wrone

Published by the University Press of Kentucky, 2003.

368 pages with notes, select bibliography and index. ISBN: 0-7006-1291-2